Wels catfish tracking system

Micol Rispoli & Lara Giordana

How to cite: Rispoli, Micol & Giordana, Lara (2025) Wels catfish tracking system. In: Dialoguing Species | Crafty Practices, https://dialoguing-species.eu/crafty-practices-archive/wels-catfish-tracking-system/, ISBN: 9791298510227

Access to the islet is through a metal gate with warning signs for livestock and guard dogs. The path is bordered by wire fences protecting the riverbanks. Carlo and Flavia carry the first replacement battery together, using a stick through its handles for balance. Holding it, they pass through the fences.

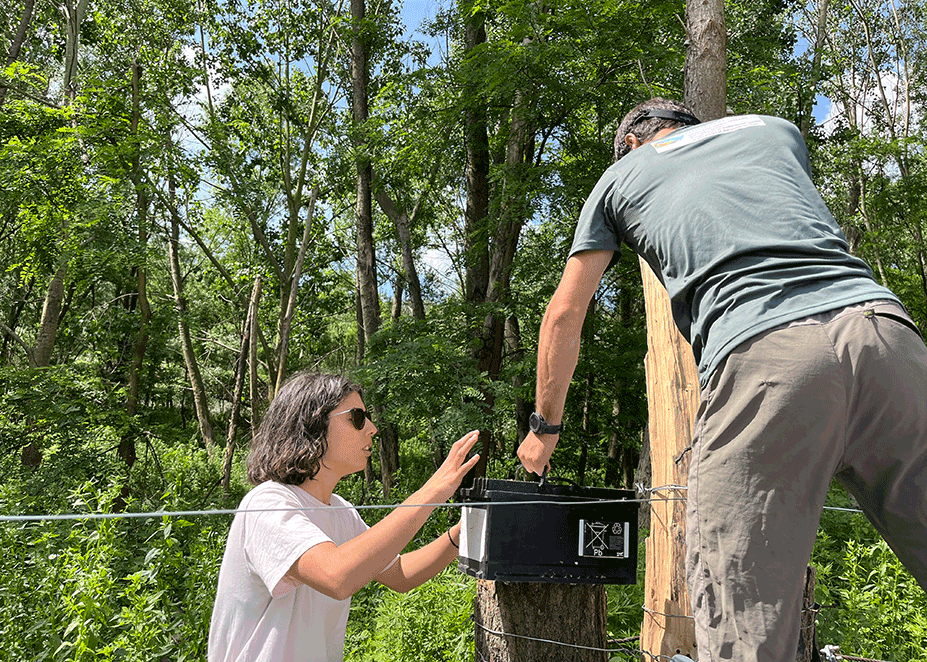

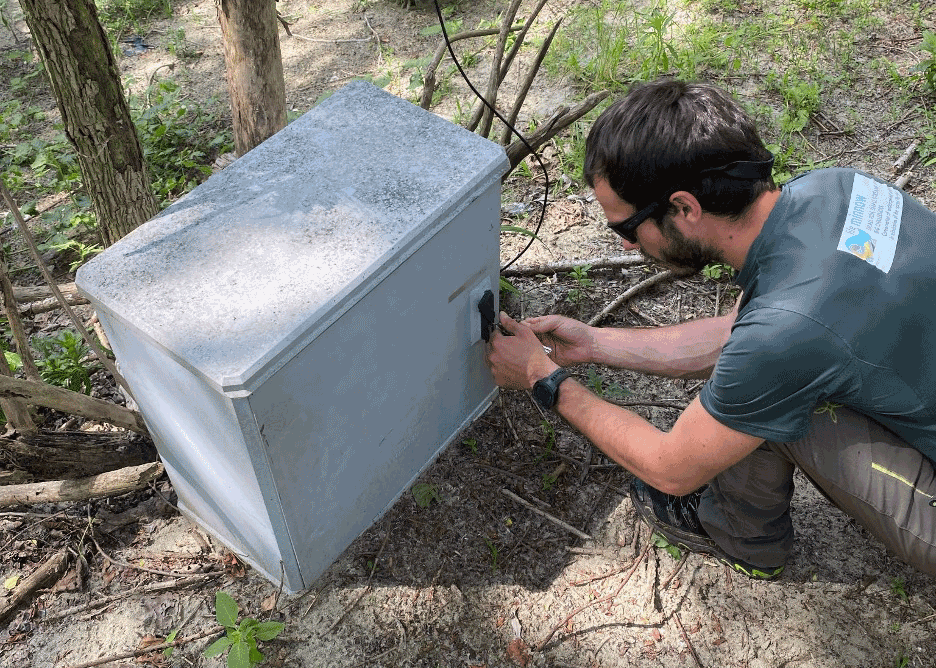

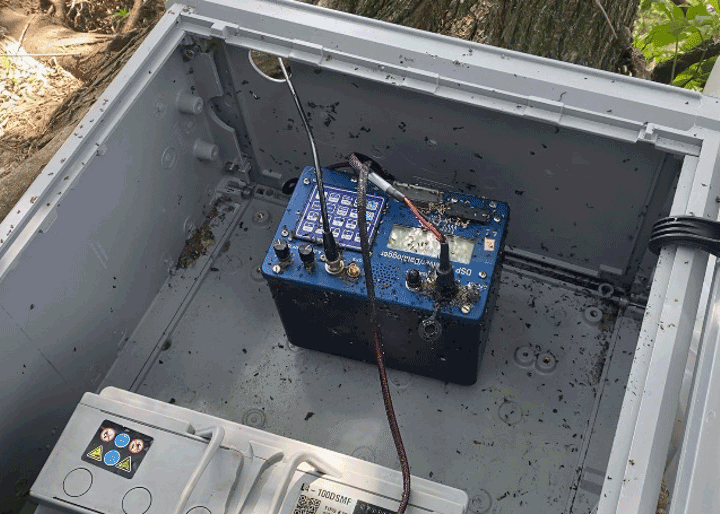

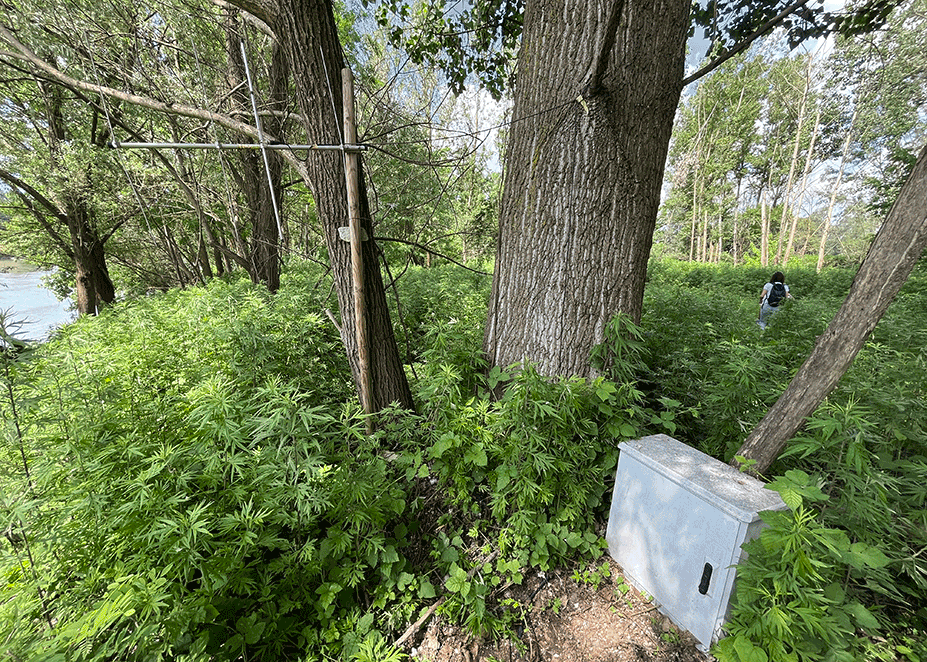

At the first monitoring station, the plastic box housing the receiver and battery is opened. The previous battery is found disconnected. “There’s always something wrong with the batteries,” Carlo says. Flavia hopes it hasn’t been the whole week without power. Carlo replaces it, reconnecting cables between antenna, receiver/data logger, and battery. The receiver scans frequencies corresponding to tags that have been installed in the fish for a year; when a tag signal is detected nearby, the device registers it. Data are stored in the receiver for several months. Downloading requires specific software from the manufacturer, which runs only on Windows. Daniel came the previous week to collect data using his computer.

At the second station, the box is covered with ants. When touched, they release a pungent smell. Carlo brushes them off and installs the new battery, remarking that they have colonized the equipment quickly, perhaps attracted by the warmth or the electromagnetic field. The third station is partially overturned. A plastic sheet has been fixed over the box to keep out rainwater. The replacement battery is fitted, and the cover resecured. The fourth station lies near the point where the boat is moored.

Carlo and Flavia pull the flat-bottomed boat to the river’s edge and tie it to a log. They carry the outboard engine from the vehicle to the shore. Besides replacing the batteries in the four fixed stations used to monitor tagged Wels catfish, boat tracking with a portable receiver and antenna is carried out. Both operations are performed weekly. The portable device/antenna provides finer localization by allowing triangulation of tag positions. Discussion turns to the tagged fish: some may have moved downstream below the dam, others could have died or been caught. One individual, tagged at 90 cm the previous year, is now likely over a meter. If it is still there, it means that for fish of that size, the dam’s fish ladder doesn’t work (Flavia says “fortunately”).

All frequencies are cleared and then re-entered in the portable receiver, one for each fish. During scanning, the receiver goes through them in sequence; when a tag is detected, the signal strength indicates proximity. As fish are located, frequencies can be manually deleted from the list. Initial detections can occur at distances up to 200-300 meters.

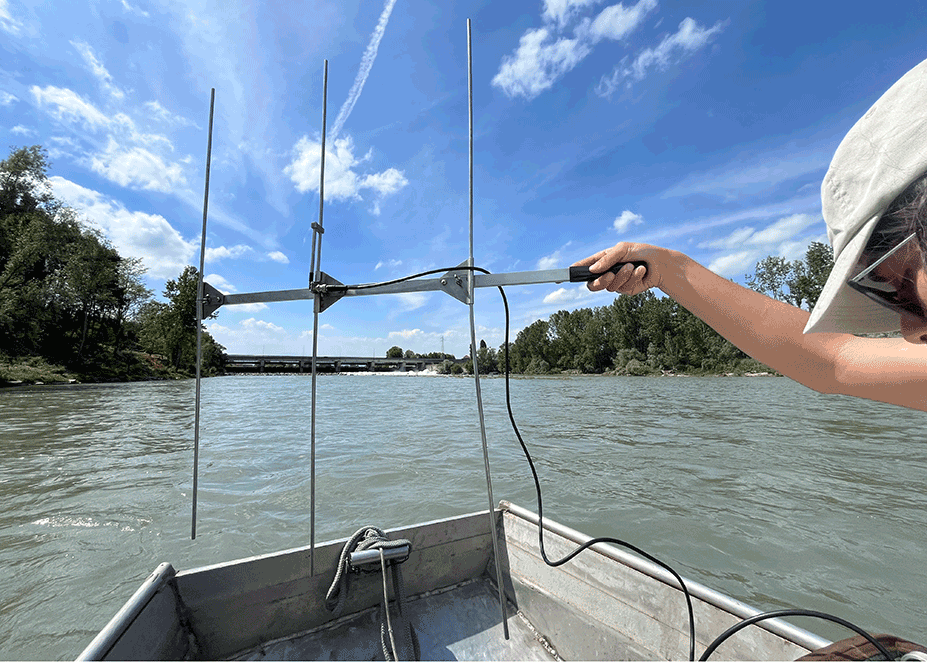

Flavia notes the date and start time of the tracking session on the data sheet fixed to the clipboard: 13:50. The data sheet lists the frequencies in ascending order, spaced about 20 MHz apart. Each fish is identified by its frequency. Carlo steers the boat toward the center of the river, moving slowly upstream. Flavia handles the antenna. It is smaller than those at the fixed listening stations. The antenna is connected to the portable receiver, which is set to maximum gain (sensitivity) to amplify the faintest signals. Flavia moves the antenna in front of her from the center of the river toward the river’s right bank, on her left.

Almost immediately, the first beep sounds. Carlo adjusts the throttle to balance movement against the current with minimal noise and disturbance. Flavia gradually reduces the gain, until the signal is just audible. If it disappears, she knows the antenna is misaligned and adjusts its orientation. The process continues through alternating adjustments of gain and direction. The volume guides her: louder beeps mean the antenna is pointed correctly and the boat is approaching the fish. When the signal grows strong, Carlo reads the coordinates from Google Maps, and Flavia records the time and location beside the tag ID on the data sheet. By 13:55, fish 481 has been located. That frequency can now be excluded from the receiver, and scanning starts again.

Fish 660 is located a few minutes later, at 13:59, in mid-river. The fish themselves are not visible, even when the water is clearer. Over the weeks, Flavia and Carlo have learnt to recognize the stretches that Wels catfish tend to favor and anticipate where the signals are likely to come from. About 90% of detections occur near the banks. The tagged catfish appear relatively sedentary, favoring sheltered areas such as submerged tree roots, branches, stones, and concrete blocks along the riverbanks. These structured habitats, along with calm backwaters, were once dominated by pike, the former apex predator, before catfish established themselves. Several tagged fish have gathered in a shallow dead-water pool, suggesting a temporary aggregation. Wels catfish are known to show social behavior and to provide parental care. In shallow waters, the male prepares a nest by clearing the bottom or using vegetation. After spawning, he lingers near the nest, fanning the eggs with his fins to keep them clean and maintaining a quiet vigil over his offspring.

Nearly twenty minutes pass before the next signals appear. Weeks of fieldwork have sharpened Flavia and Carlo’s ability to interpret signal intensity, attuning them to the subtleties of the river’s microhabitats. Some signals demand patient listening, especially where rocks interfere with transmission. Continuing upstream, the riverbed becomes shallower, and the dam-bridge ahead is now clearly visible, its gates lowered. Carlo must pay close attention to water depth and submerged obstacles to avoid damaging the outboard propeller. This limits how closely the boat can approach the banks and the dam. The signal from fish 642 comes from the direction of the dam, but approaching further would be risky. The position is recorded with the note “low precision,” indicating an estimated range of about fifteen meters.

The boat turns and heads downstream. Fish 522 is located just upstream of the lowest dam that marks the edge of the tracking area. The origin of the Wels catfish in this stretch of the river is uncertain: they may have been introduced deliberately, or small juveniles could have ascended the fish ladder built to mitigate the barrier effect of this dam.

About three hours have passed. Tracking will be repeated after dark; at this time of year, the sun sets after 21:00. Eighteen of the tagged fish have been located. With several hours before the nighttime session, Carlo decides to walk downstream to test the hypothesis that some tagged fish may have passed the dam. The tracking equipment draws the curiosity of two young anglers, who come over to ask questions. There is no trace of the missing catfish.

At 22:00, Carlo and Flavia resume boat tracking, using a new data sheet. Navigating in the dark requires even greater caution, and approaching detection points becomes more delicate.

In this urban stretch of the Po River, located northeast of Turin and lying between two dams, radio telemetry allows researchers to study the movement of Wels catfish. Using automatic listening stations and weekly boat tracking, they map movements across the pre-reproductive and reproductive seasons, measuring linear range, travel between river reaches, day/night activity, and habitat preferences for each tagged fish. The study of Silurus glanis – the Wels catfish – is conducted as part of the Life Minnow project. The results are expected to be used to limit the spread of this non-native species, which is considered highly invasive in the Po basin.

Photos and video taken at San Mauro Torinese (TO) on 03/06/2024. Pictures 1, 3 & 4 by Micol Rispoli; pictures 2, 5, 6, 7 & video by Lara Giordana